Historical ArtAt first glance, this album from a past QBO sale appears to be a small book about some obscure ‘watercolour’ painter, probably containing OK prints and a dry biography listing a bunch of dates and names. (yawn)

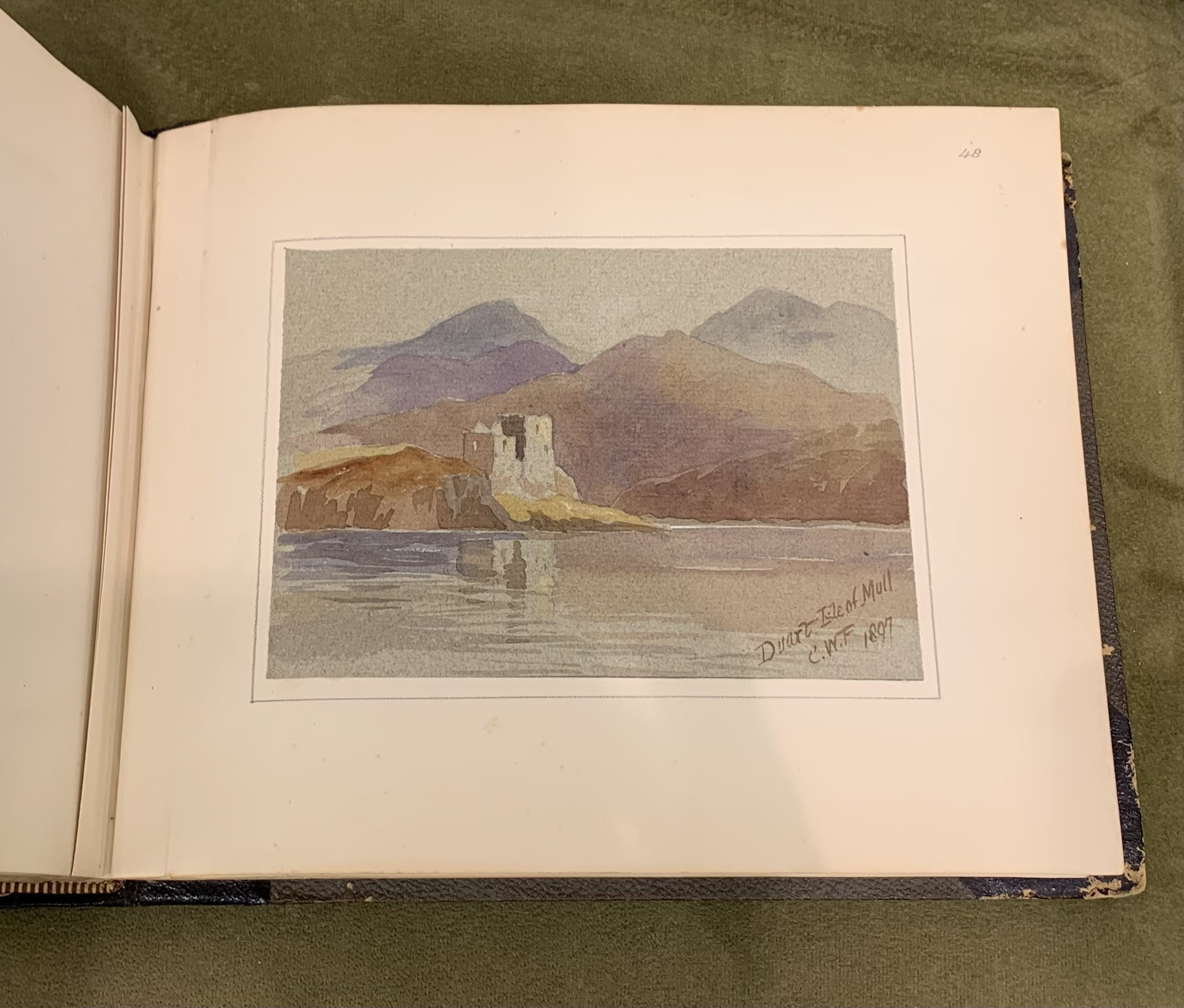

Not so! This is a sample book that the artist himself carried with him in the late 1800s, containing around 45 ORIGINAL watercolors and pencil sketches. They are British landmarks, architecture or vessels. Each is notated with title and date, sometimes twice (once on the original, with more information added to the page the painting was glued onto.) Each was done separately, then the rippled edges were trimmed away and it was ‘tipped in’ to the book, that is, they weren’t painted directly in the folio, they were glued in upon completion. So it is interesting to note that both finished paintings and quick sketches are meticulously preserved here.

This is because the artist, one Charles W. Fothergill, was demonstrating just what he could produce under varying circumstances and time constraints with a high degree of accuracy, something crucial to his profession. Fothergill does not have the career trajectory that we now expect of an artist. AT ALL. Today we think of painting as an impractical, if not impossible way to make a living and the cliché artistic temperament as driven by emotion, insecurity and ego, like Picasso, Dali or Van Gough. Not so with Captain C.W. Fothergill. Fothergill received his training as a painter in the British Royal Military Academy and went on to serve at the RMA, Sandhurst, teaching young officers how to accurately render landmarks, architecture and crucial transport such as ships. His notes on laying down contours and instructions for military sketching and surveying are included in 1880s military documents.

|

| So important was this skill to 1800s British military operations that both the British Army and the British Navy trained and fielded their own painters who were given officer rank. Although photography was invented in 1839, it was many decades before it was practical to carry cameras on operations. Neither caustic, hard-to-get chemicals nor portable darkrooms were needed to produce a militarily useful rendering, just a well-trained painter with paper, a paintbox, a steady hand and a good eye. That was Captain Fothergill.

None of Fothergill’s works were created from imagination; all are subjects he observed in front of him and are carefully noted as such in their titles. Although he made no big splash as a fine artist, historians appreciate Fothergill’s visual records and thus today some of his paintings are found in local museums in English towns, not as ART with a capital A, but showcasing important local landmarks like historic bridges or churches. You can compare his works to photos taken today of the same view and see both how dead-on accurate they are, and make note of changes that have taken place over time.

And, although Fothergill left behind no publicly available letters or diaries, we can trace his journey through works sold at auction: paintings of England, Scotland, France, India and Canada. The Captain’s discerning eye took him interesting places. He later lived in Cranbrook, Kent and exhibited work at the Suffolk Street Galleries and the Royal Academy in 1900. Today his modest but eminently pleasing art is sold in the U.K., Canada, France and the U.S.

So how did his beautiful folio book make it all the way to Oregon? No idea. All we know is that he passed through our Beehive and then went back out into the world again. |