Transcontinental

|

The Valley and Siletz 40.5 mile line ran through Polk and Benton counties. It connected riverside Independence with the logging town of Valsetz (named after the Valley and Siletz), supplying the Willamette Valley with lumber. But the railway changed hands many times as needs shifted, and its troubles were compounded by legal issues. Boise Cascade ended up owning the line for a few decades before closing it in 1978. The line was re-opened from 1985 to 1992 by Dave and Mike Root to serve the Mountain Fir Lumber Company, but it has now lain dormant for 30+ years, shedding its spikes.

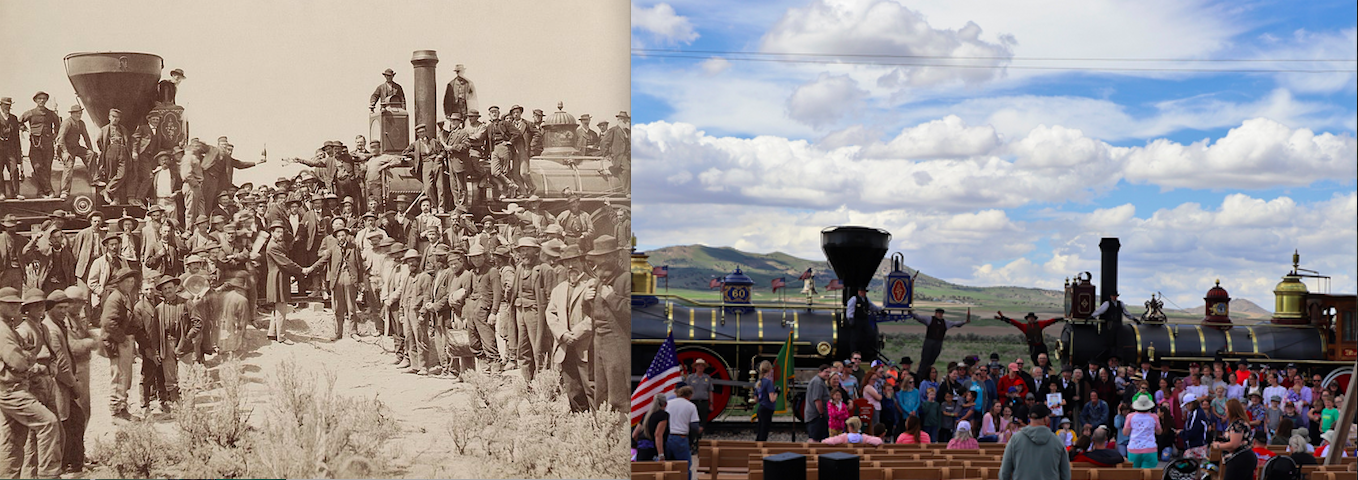

In contrast, this Golden Spike celebrated the 160th anniversary of the first Transcontinental Railroad in the world which connected Alameda, California, on the west coast, to the nation’s already existing eastern lines. The gold-painted spike is probably from the Golden Spike National Historical Park in Utah, where the two lines coming from East and West (and bankrolled by competing companies) were joined together on May 8th, 1869 to complete the Transcontinental.

The final spike to be driven in was solid gold, made by a friend of Central Pacific President Leland Stanford. Stanford built his rail line by overworking his Chinese, Irish, Mormon and Civil War veteran laborers, which even back then drew some harsh criticism. The ruthless mogul’s investment made him a vast fortune, which he later used in part to found Stanford University. In 1978 when the student body decided to retire their “Indian Chief” mascot, a hearty majority voted for the new mascot to be the “Robber Baron”, a term coined for the brutal railroad tycoons by 1800s reporters. Sadly, the university was not amused and 45 years later it still has no official mascot but at least we can admire Stanford’s Golden Spike. 😉 |