This MG convertible will be on offer at our upcoming Salem sale. With its sleek lines, low-to-the-ground profile and muscular engine, Road & Track magazine estimated in 1961 […]

Diminutive Akan Bronze Goldweight Demon

Standing less than 4″ tall, this tiny demon packs plenty of charismatic menace. A recent arrival to QBO, it will be on offer at our upcoming Beehive Sale […]

Lighthouses and House Insulation

These two seemingly unrelated items from different QBO sales actually have something sweet and natural in common. This 4″ x 4″, gently-scented sachet commemorates the Marshal Point Lighthouse […]

Year of the Dragon

Queen B is finally celebrating The Year of The Dragon one month late with this scaly menagerie from past sales. We have two ‘flavors’ here; Asian and European, […]

Blackthorn Walking Stick or Weapon

These two walking sticks from our last Estate Sale are an elegant example of how artisans refine their work or not; one has been sanded, polished and topped […]

Wedgwood Renaissance Red

This elegant dining set will be on offer at our upcoming QBO Estate Sale. It has the look of fine antique china because it IS fine bone china, […]

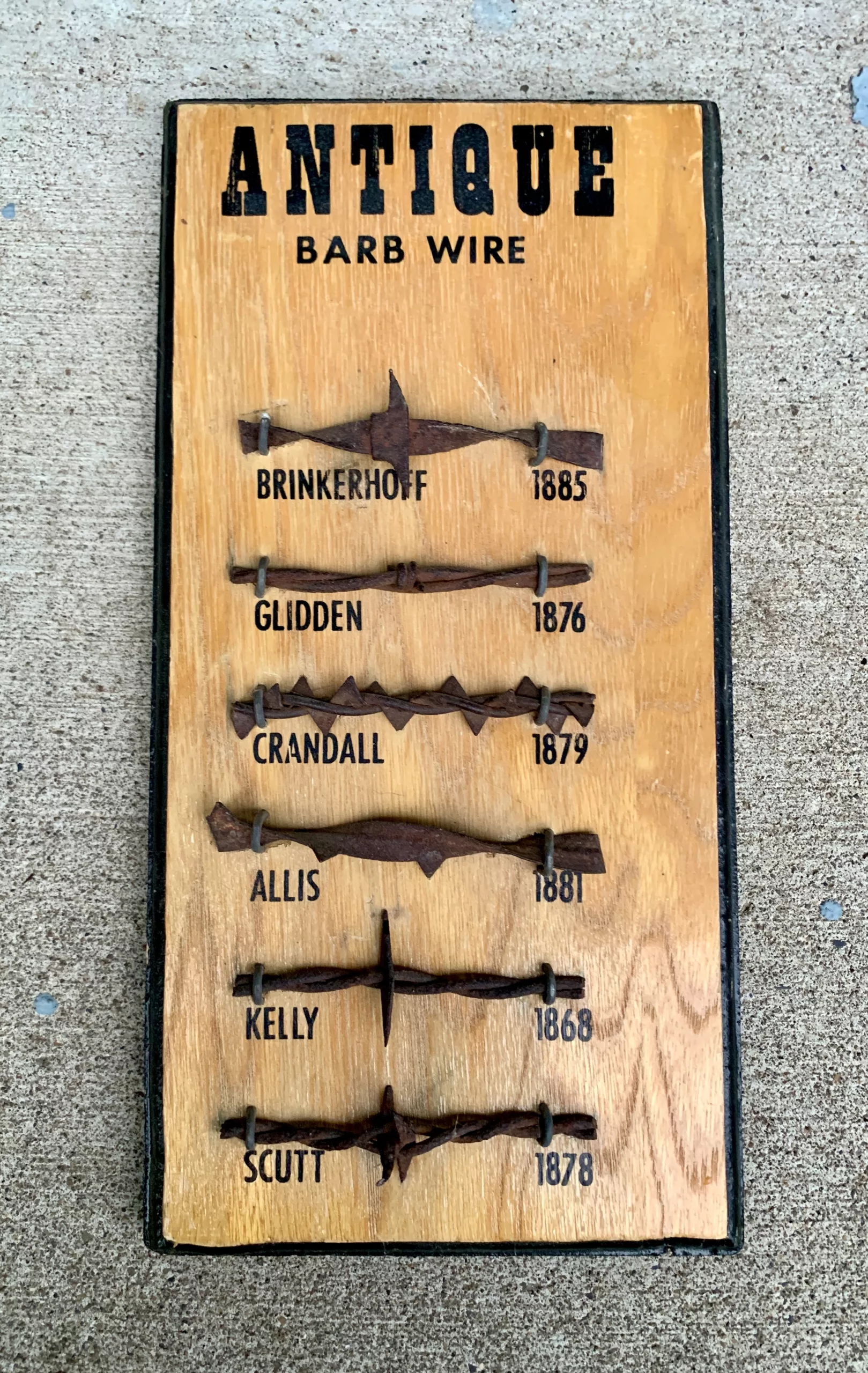

Antique Barb Wire Variants

Tuesday Treasures tells micro-histories of QBO items from the ordinary to the vanishingly rare, but this is one of the few actually designed for telling history: an Antique […]

G.I. Joe and G.I. Elmer, as Ducks

This cute G.I. Joe “Unbeaten Team” toy sold at our last QBO estate sale. Don’t be misled by the visible 1918 date, it was patented around 1945. Push […]

Lucifer, Match Safes, Strikers and Boxes

These two boxes from past QBO sales are wall-mounted Match Safes. They kept matches close at hand in the days of woodstoves. Early gas stoves had pilot lights […]

Tasty Shish Kababs

Who’s up for shish kabab grilled on (mostly) Turkish skewers from QBO? Folklore claims Turkish soldiers grilled meat on their swords over campfires during the invasion of Anatolia, […]